The dragon is one of the traditionalChinese zodiac animals and the only one from myth and legend, holding a uniqueand mysterious position in Chinese culture. Since ancient times, the dragon hasbeen regarded as a spiritual symbol of the Chinese nation, representing theunique cultural cohesion and accumulation of the Chinese people. As a mythicalcreature closely linked to the Chinese nation, ancient ancestors believed thedragon was an auspicious beast that mediated between heaven, earth, gods, and humans,capable of summoning wind and rain and predicting fortune and misfortune. Thus,they revered it deeply and depicted its image in various forms. As early as theearly Neolithic Age, ancestors had dragon-worshipping customs. For example, in1987, a "dragon" pattern made of white clam shells was unearthed atthe Xishuipo site in Puyang, Henan; in 1994, a 4.4-meter-long dragon made ofpebbles was found at the Jiaodun site in Huangmei County, Hubei; and in 1995, a19.7-meter-long dragon made of red stones was discovered at the Chahai site inFuxin County, Liaoning. The Shang and Zhou dynasties marked thepeak of bronze ware development, when people skillfully adorned numerous bronzevessels with dragon motifs, integrating the divine beast with the utensils.Dragon patterns thus became one of the most important decorative motifs ofChina’s Bronze Age.

As a decorative element on bronze ware, thedragon first appeared during the Erligang period of the Shang Dynasty. Later,from the late Shang Dynasty, Western Zhou, Spring and Autumn, to the WarringStates period, various forms of dragon patterns emerged. These included notonly bronze dragon-shaped vessels but also dragon motifs. When depicting thefrontal image of a dragon on bronze ware, the nose typically served as thecentral axis, with eyes on either side and the body extending sideways. Duringthe Shang Dynasty, bronze dragon patterns primarily reflected awe of thedragon’s mysterious power, characterized by an archaic, enigmatic, and majesticstyle, dominated by diverse kui dragon patterns and coiled dragon patterns. In the early Western Zhou Dynasty, bronzedragon patterns largely 延续了 the late Shang style, withvarious kui dragon patterns, coiled dragon patterns, flower-crowned dragonpatterns, two-headed dragon patterns, and double-bodied dragon patternsremaining prevalent. By the mid-Western Zhou, people began to pursue the artisticaesthetics of bronze dragon patterns: kui dragon patterns gradually faded,while bird-bodied flower-crowned dragon patterns (with dragon bodies and birdtails) and 回首 dragon patterns (with separated bodiesand tails) became widespread.

During the Spring and Autumn and WarringStates periods, dragon patterns on bronze ware grew more realistic, shiftingfrom the rigorous and powerful style of the Shang and Zhou dynasties to alively and fresh one. The mysterious aura of the motifs diminishedsignificantly, and dragons began to be depicted with four legs, enhancing theirelegant and vibrant appearance. Meanwhile, lively and delicate panchi (coiledsmall dragons) and panhui (coiled small snakes) patterns emerged. After the Qinand Han dynasties, the dragon’s image gradually standardized and stabilized.

The evolution and formation of the dragon’simage embody the wisdom of ancient people and the essence of national culture.It is the most widely circulated myth and the most influential cultural symbolin Chinese civilization. The dragon symbolizes not only power and nobility butalso wisdom, mystery, and auspiciousness. For thousands of years, the dragontotem has permeated every aspect of the Chinese nation, becoming a symbol ofChina, the Chinese people, and Chinese culture. For every Chinese, the dragon’simage is a symbol and a bond of blood and emotion.

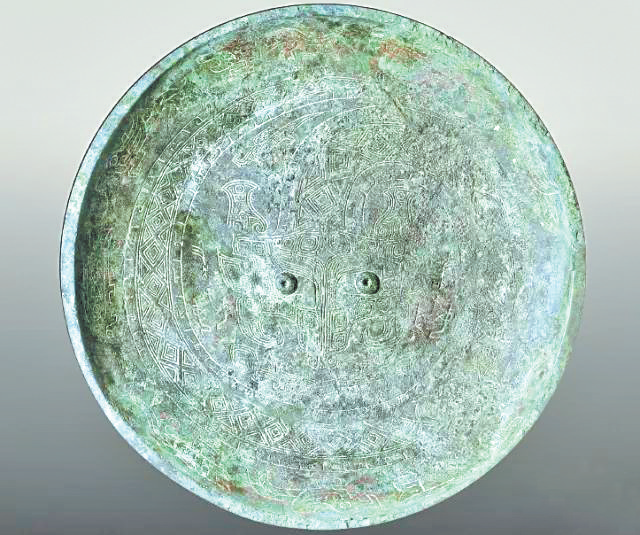

The Western Zhou large bronze round ding inthe collection of the Gansu Provincial Museum stands 60 cm tall with a 50 cmdiameter. Its upper abdomen features six sets of beast-faced patterns separatedby short five-toothed 扉棱 (vertical ridges) that serveas nose wings; the separated parts of the beast faces are complete kui dragonpatterns with tails and claws. Kui dragon patterns, also known as kui patterns,rank second only to beast-faced patterns. After beast-faced patterns declined,kui dragon patterns once became the main decorative motifs on bronze ware,prevalent during the Shang and early Western Zhou dynasties. Shang kui dragonshave short bodies and often appear as standalone motifs, mostly in a 屈曲 form; Western Zhou kui dragons have longer bodies, usually arrangedin a continuous pattern or coiled together. This ding is 浑厚,solemn, magnificent, and exquisitely decorated, representing asuperb example of pre-Qin ritual vessels and the largest and most prestigiousbronze ding unearthed in Gansu to date. The Qin Gong gui (a food vessel) in theNational Museum of China was unearthed in Tianshui, Gansu, in 1921. The gui isround, with its lid and body forming a slightly flat, circular shape; the lidhas a circular handle, and the edge of the lid and the lower part of the vesselmouth are adorned with interlocking panchi patterns. Panchi patterns, alsocalled intertwined dragon patterns, were popular from the mid-Spring and Autumnperiod to the early Warring States period, consisting of two or more small dragonsintertwined to form decorative units densely covering the vessel’s surface. The Fu Hao basin, unearthed from the Fu Haotomb in Henan, has a diameter of approximately 36 cm and weighs 5.9 kg. Theouter wall of the basin’s belly is decorated with a continuous band of kuipatterns, and the outer wall of the feet with a continuous band of taotie(mythical beast) patterns. The inner wall features a coiled dragon as the mainmotif, with the dragon’s head at the center, a kui pattern beneath it, and theinscription "Fu Hao" cast on either side of the head. The coileddragon is surrounded by a circle of beast patterns, making the decorationextremely ornate.

The largest bronze dragon, housed in theShaanxi History Museum, measures 240 cm in total length, 100 cm in width, and40 cm in height. Its body is hollow, with a slightly square head, protrudingeyes, upturned nose, and open mouth; the body is adorned with fish-scalepatterns, and the tail curls into a hollow cone that can be inserted into acolumnar object. The bronze dragon was cast in separate parts and weldedtogether, boasting a massive size, majestic presence, and exquisitecraftsmanship, making it the largest bronze dragon ever unearthed. This dragonshares similarities with the hollowed-out coiled dragon drum base in theShanghai Museum; such large and elaborate bronze artifacts likely served asbases for large musical instruments in the Qin court. The hollowed-out coiled dragon drum base inthe Shanghai Museum stands 30 cm tall and weighs 37.9 kg. On its hemisphericalsurface, 12 coiled dragons of varying sizes climb and bite each other. Three ofthe dragons have heads and bodies facing downward, with tails coiled around thedrum-inserting cylinder, their mouths gripping the bodies of dragons climbingon the foot ring; three have heads and bodies curved upward, with tails coiledon the foot ring, their mouths biting the tails of the downward-facing dragons;and three encircle the drum base, climbing on the upper part of the foot ring,their mouths biting the tails of the upward-facing dragons. Under their raisedtails are three small dragons with sculpted heads holding rings in theirmouths, their bodies depicted in high relief on the drum base. The largedragons have hollow circular eyes, which may have once been inlaid withornaments, now lost; the ends of their horns are hollow grooves that may haveheld similar decorations. The base of the drum is also carved with numerouscoiled dragon patterns. The earliest bronze round ding inscribedwith the character "long" (dragon) is the Shang Dynasty Zi Long Dingin the National Museum of China, standing 103 cm tall. It has a majestic,full-bodied shape and is the largest round ding from the Shang Dynasty everdiscovered. The inner wall of the Zi Long Ding clearly bears the inscription"Zi Long" (Master Dragon), giving it its name. The character"Zi" (master) is in the upper left corner, small and carved in solidlines; "Long" (dragon) is in the lower right, outlined in doublelines, resembling an upright dragon with a right-curling tail, an open mouth,round eyes, and a prominent bottle-shaped horn not connected to the head. The"long" inscription on the Zi Long Ding is confirmed as the earliest occurrenceof the character in a bronze round ding inscription. In addition to theinscribed dragon image, the upper abdominal patterns of the ding also depictdragons. The dragon-patterned si gong (a winevessel), also known as the dragon-shaped gong, dates to the late Shang Dynastyand is now in the Shanxi Museum. It stands 19 cm tall, 44 cm long, and 13.4 cmwide, with an overall dragon shape: the front end is a dragon head with baredteeth, raised snout, open mouth (serving as the spout), and thickupward-pointing horns, giving a ferocious appearance. The rear end is flat andbroad, with a long lid on top and a knob in the center; the rim of the vesseland the lower part of the mouth have two pairs of loop handles, and therectangular foot ring has notches on all four sides. The lid is decorated withwinding dragon patterns, connecting to the front dragon head and set againstspiral patterns, creating a cohesive design. The main patterns are alligatorpatterns and kui dragon patterns, with heads facing opposite the dragon head,exuding dynamism. The foot ring is adorned with opposing kui dragon patterns.This unique, ingeniously designed, and ornately decorated vessel is a raretreasure among Shang bronze ware.

The tiger-and-dragon-patterned zun (a winevessel) in the National Museum of China stands 50.5 cm tall and weighs 26.2 kg,making it a relatively large wine container. Its shoulders feature three vividcoiled dragons crafted in a combination of round carving and relief, withwinding bodies, protruding heads, double horns, broad snouts, large mouths, andwide-open eyes. The abdominal pattern depicts a tiger head with two bodies,with a human figure between the tiger mouths, whose head is held in the tiger’sjaws. Below the tiger bodies, separated by 扉棱,are beastfaces formed by opposing kui dragons. The main motifs—dragons, tigers, andhumans—are solemn, stable, strange, and mysterious; particularly, the dragonand tiger heads protrude dramatically from the vessel’s exterior using castingtechniques, appearing more powerful and rugged than high relief, exuding anintimidating aura. The round mouth of the zun symbolizes heaven, while thedivine dragons on the shoulders roam the sky; the tigers with bared fangs guardthe earth. The zun was cast using 18 master molds and welded twice, forming aseamless whole. Exquisitely crafted with sleek lines, it is a masterpiece ofShang bronze ware. The largest round ding of the Western ZhouDynasty, housed in the Shaanxi History Museum, is the Chunhua Da Ding (GreatDing of Chunhua). It has a majestic, solid shape, retaining the late Shangstyle of thick walls, grand proportions, and a solemn demeanor. Standing 122 cmtall with an 83 cm diameter, 28.6 cm tall ears, 54 cm deep belly, and weighing226 kg, it is the largest and heaviest Western Zhou bronze ware ever found andthe largest round ding from the Western Zhou Dynasty unearthed to date. Due to itssize and weight, in addition to the two ears on the rim, the vessel has threeears on its waist, resembling the handles of wine vessels. Most dings have onlyrim ears; the three beast-headed tongue-shaped handles on the Chunhua Da Ding’swaist are unprecedented in unearthed bronze dings, earning it names like"Beast-headed Tongue-handle Ding" and "Five-eared Beast-facedDing." Beyond its unique three ears, the combination of dragon patternsand beast-faced patterns on its waist is distinctive: each of the three sideshas two kui dragons, which, together with the central 扉棱,form a beast face (taotie pattern) with the 扉棱 as the nose. Below the 扉棱 of each beastface is a lifelike relief of a bull’s head, as if the taotie is about to devourthe bull, serving as a deterrent. Hence, it is also called the"Bull-headed Kui Dragon Ding" or "Dragon-patterned Ding."

The Lai he (a water vessel) unearthed inBaoji, Shaanxi, resembles a modern flattened round pot, with a flat circularbody and a phoenix-headed lid on its rectangular mouth. The phoenix raises itshead, with a slightly curved beak and outstretched wings, as if about to takeflight. The vessel and lid are connected by a tiger-shaped chain with tworings; the tiger crawls upward, with its head turned left and tail curled. Thestraight spout ends in a dragon head, and the handle is shaped like a dragonhead spouting water downward, supported by four beast feet. Both sides of thebelly have identical three-circle patterns: from the outside in, they arevariant kui dragon patterns, double ring patterns, and coiled dragon patterns.The Lai he is a ritual vessel that incorporates phoenixes (flying in the sky),tigers (running on land), and dragons (swimming in water) as messengersconnecting heaven, earth, and humans, unifying the three realms. The WesternZhou people regarded animals as divine beings with immense power; thus, animalmotifs on bronze ware, in addition to religious and ritual significance, alsoheld political meaning. Nobles used the mysterious and solemn animal patternsto inspire reverence and awe in the ruled, consolidating their status and authority,while also embodying the auspicious symbolism of "dragons soaring, tigersleaping, and phoenixes bringing prosperity."

|