This post was last edited by AyaCica at 2025-8-21 10:02

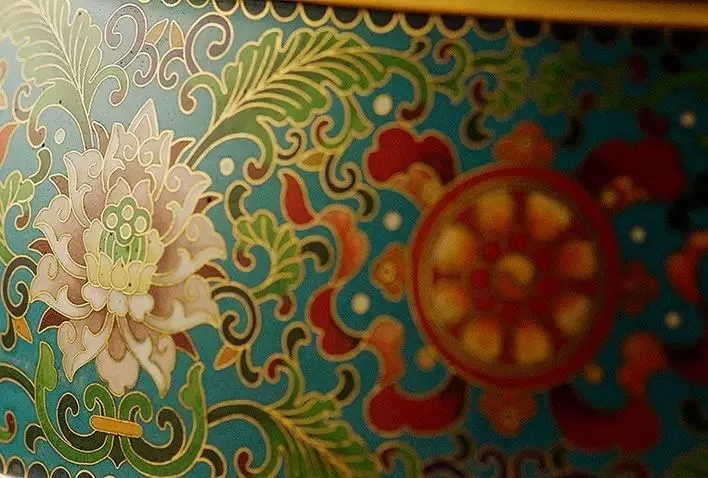

Cloisonné, also known as cloisonné enamel, is a unique craft combining porcelain and copper. To make cloisonné, one first shapes a base from red copper, then uses flat, thin copper wires to form intricate patterns on the copper base, which are adhered in place. Next, enamel glazes of different colors are inlaid and filled within the patterns. After this step comes repeated sintering, polishing, and gilding. It can be said that cloisonné craftsmanship integrates bronze techniques, porcelain craftsmanship, and traditional painting and carving skills, making it a culmination of Chinese traditional crafts.

Legend has it that in the early Yuan Dynasty, a fire broke out in the imperial palace, reducing the Golden Hall and countless rare treasures to ashes. Amid the ruins, however, a colorful, shimmering vase emerged. Courtiers, astonished, presented it to the emperor, claiming it was a gift from heaven.

The emperor was enchanted by the vase and immediately issued an edict: all skilled craftsmen in the capital must replicate it within three months, on pain of death. This sent the craftsmen from eighty-one workshops in the capital into a frenzy.

Puzzled and unable to decipher the heavenly craft, they turned to “Qiaoshou Li” (“Skillful Hand Li”), the capital’s foremost craftsman. Legend held that he was a descendant of Nüwa, the goddess who created humanity, and earned his reputation for crafting extraordinary works.

Soon, Qiaoshou Li reported that Nüwa had appeared to him in a dream, draped in a cloud-like robe and standing on auspicious clouds. She said: “The vase shines like a blooming flower, all thanks to skillful hands that ‘plant’ the bloom. Without bletilla, the flower won’t open; without the eight-trigram butterfly, it won’t come; without enduring water immersion and stone grinding, how can spring linger forever?”

Qiaoshou Li unraveled the dream: the palace fire had melted gems and gold in the Golden Hall, forging the vase. The emperor then decreed that all such vases crafted by “Qiaotiangong” (divine craftsmanship) would belong to the palace. Since this rare treasure was “burned out” in the imperial palace, people called it “Qibao Shao” (“Miracle Treasure from Burning”).

Nüwa’s words—“Without bletilla, the flower won’t open; without the eight-trigram butterfly, it won’t come; without enduring water immersion and stone grinding, how can spring linger forever?”—refer to the five key steps: wire inlaying, glaze filling, firing, polishing, and gilding.

Wire Inlaying

Tweezers are used to pinch and bend flattened thin red copper wires into elaborate patterns, which are then adhered to the copper base using bletilla glue. Silver solder powder is sifted over the wires, and the piece is fired at 900°C, fusing the copper wire patterns firmly to the base.

Master craftsman Mi Zhenxiong insists: “The primary beauty of cloisonné lies in its craftsmanship. Every step, from base-making to polishing, must be done by hand.”

Watching him work the wires is a serene experience. The master presses the red copper wire with his fingernail while manipulating tweezers to stretch, bend, and loop it. The shape of the design and the curvature of each line depend entirely on the craftsman’s skill.

Glaze Filling

After wire inlaying, the base undergoes soldering, acid washing, flattening, and wire straightening before moving to glaze filling.

Artisans use small shovel-like tools (hammered from copper wire) to fill the soldered copper wire frames with pre-prepared enamel glazes, matching the colors marked in the design. The glaze must be applied 饱满 and evenly; the craftsman controls the intensity of colors, dabbing and 吸干 excess glaze with absorbent cloth. The number of glaze layers—each critical—determines the pattern’s light and shadow, and the subtle transitions between hues.

Firing

Once the base is fully filled with glaze, it is fired in a furnace at approximately 800°C, using mineral stone powder as fuel. The granular glaze melts into a liquid, which solidifies into vibrant color on the base as it cools. Since the glaze shrinks below the copper wires after firing, this process is repeated four or five times until the glaze is flush with the wires.

Polishing

Polishing involves three stages: rough sandstone, yellow stone, and charcoal are used to smooth uneven glaze. Any imperfections require re-glazing, refiring, and re-polishing. Finally, charcoal and scrapers are used to brighten the copper wires, edges, and rims where no glaze covers.

Gilding

The polished cloisonné is acid-washed, cleaned, and sanded before being submerged in a gold-plating bath. Electric current is passed through the bath, and within minutes, a layer of gold adheres to the metal parts. After rinsing, drying, and mounting on an exquisitely carved hardwood base, the resplendent cloisonné piece is complete—radiating elegance and dignity.

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, cloisonné has evolved with the times, expanding into two main categories: cloisonné and filigree cloisonné. Cloisonné includes gold-ground and blue-ground varieties; filigree cloisonné encompasses gold-ground, silver-ground, and blue-ground pieces, as well as gold and silver “pao si” (coiled wire) works. Admired worldwide, cloisonné has become an indispensable home decor item and a timeless craft.

In 2011, a pair of “Qing Qianlong Imperial Gilt Copper Cloisonné Enamel Boxes for Spring Longevity” sold for 42.73722 million yuan at Christie’s Hong Kong. Since then, cloisonné has become a collector’s favorite. In the rush to profit, many prioritize price over craftsmanship—using less copper wire, skipping steps, or even mass-producing machine-made imitations that merely resemble cloisonné, yet still sell wildly.

Objects cannot speak; their value and legacy depend entirely on human intention. For 600 years, cloisonné’s elegance has defied time—but it may fade if people lose their reverence for tradition. We have reason to believe that thoughtless, unreflective admiration is destructive to cloisonné craftsmanship. The scholar Lin Huiyin, who cherished cloisonné, urged on her deathbed: “Cloisonné is a national treasure; do not let it perish in New China.” Indeed, national treasures—prides of the nation—should shine alongside the world, without regret.

|